As a breathing coach, one of the most surprising things people hear from me is the instruction to breathe less. We’re used to breathing practices being about deep, big, full, fast breaths, about breathing more. Why on earth would I suggest that people breathe less?

When we are kids first learning about breathing at school, we are taught that we inhale oxygen (O2) and we exhale the waste gas carbon dioxide (CO2). As with all things that we learned as children, it’s more complicated than that.

We breathe in air. Air is a mixed gas that’s composed of around 78% nitrogen, 20% oxygen, less than 1% argon, and the last 1% a mixture of at least 12 other chemicals. Water vapour is also usually present in the air, making up anywhere from 1-5% of the total (which of course changes the other percentages). Only about one fifth of the air you inhale each breath is the oxygen you need, and you don’t absorb all of the oxygen you breathe in. Depending on how quickly you are breathing, if you are sitting or running, you’ll absorb 15-25% of the oxygen you inhale. At this rate, your oxygen saturation will likely be somewhere between 96% and 100%, meaning that all of the possible carriers of oxygen to your cells (hemoglobin) will be full of oxygen. So, what do all of these numbers mean? Well, every time you take a breath, only 5% of that breath is absorbed by your body — it takes in all the oxygen it can handle, all it needs with only 5% of that breath.

What happens when you breathe more? If you are sitting still, breathing big breaths won’t get any more oxygen into your body than if you were breathing quietly — there is only the same amount of space on the hemoglobin to carry oxygen to your cells. As you start to move more, from sitting to standing, to walking, to jogging, to running, your need for oxygen increases as you use it to make energy. Your breathing will naturally increase to accommodate that need.

There’s something else that happens as you begin to breathe more: you also exhale more carbon dioxide (CO2). Remember, we take in O2, and send out CO2. Between an inhale and the exhale, several chemical reactions take place in your cells (which together are called metabolism) making this change. After the O2 has made its way to your cells, it joins with sugar and the result is energy (in the form of adenosine triphosphate or ATP), water, and CO2. As each cell in your body metabolises O2 and sugar into ATP, water, and CO2, the level of CO2 rises. When the CO2 levels hit a certain point, it triggers breathing — inhalation, and then exhalation — and then the body goes back to watching the CO2 levels, waiting for it to reach the point at which breathing begins again. Too much CO2 is not good for the body. However, too little CO2 is also not good.

There are some popular breathing practices that have people breathe a lot of really big breaths, lowering CO2 to a very low level, followed by going in water. This can result in Shallow Water Blackout, and is incredibly dangerous. If CO2 levels are too low before going in water, you will run out of oxygen before CO2 triggers the sensation of needing to breathe. When you run out of oxygen, you pass out. If you are in water when you pass out, you will drown. This happens to people every year, particularly in the summer when people are spending time outdoors in pools, but you can also drown this way in a bathtub.

The idea that CO2 is merely a waste product is an oversimplification that has become a myth. How many times have you been in an exercise class and been instructed to breathe lots of big breaths to fill your body with oxygen and get rid of all the toxic carbon dioxide? This idea that blowing off more CO2 is beneficial for your body has pervaded the exercise world and popular understanding of how our bodies work. It’s the Goldilocks Principle. We need CO2 in our bodies: not too much, but not too little. We need just the right amount of it. CO2 has lots of jobs, including relaxing smooth muscles, supporting kidney function, regulating blood flow, and balancing the pH of your blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

Do you have cold and hands and feet regularly? That’s likely because you’ve been breathing just a little bit too much. If you are one of these people, try this simple exercise. Close your mouth, and breathe only through your nose. Keep your breath quiet and small, but not uncomfortably so. After each exhale, pause for about 2-3 seconds. Make sure that the pauses aren’t making the next breaths larger. Do this for a couple of minutes. Are your hands and feet still cold? Hopefully, they have warmed up a little bit. That’s because the CO2 levels rose slightly during that period of slower breathing, and you had enough CO2 to relax the smooth muscles that make up the capillaries, the tiny blood vessels, in your hands and feet.

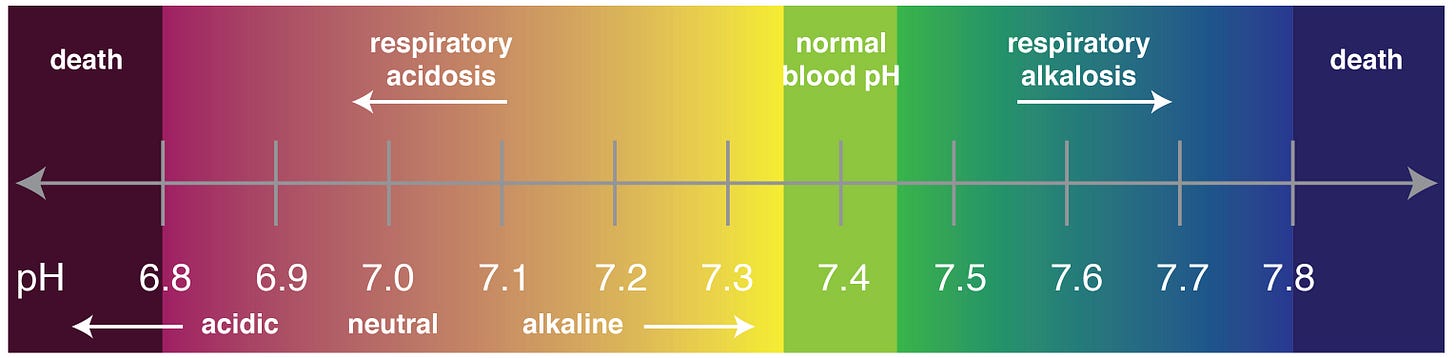

In 1904 a Danish physiologist named Christian Bohr discovered what has come to be known as the Bohr effect. It describes the relationship between blood pH (how acidic or alkaline the blood is) and how oxygen attaches to hemoglobin. Blood likes to be at a pH of 7.4, and it moves between 7.35 and 7.45 regularly. That’s a really small window, and your body will do just about anything to keep the blood there. When blood pH becomes too acidic (a lower number) hemoglobin doesn’t pick up oxygen to carry it to cells. At the other end of the scale, if blood becomes too alkaline (a higher number) hemoglobin picks up oxygen, but won’t let it go when it arrives at its destination. At pH levels of 6.8 and 7.8 cells start to die. If you don’t have enough CO2, the blood pH starts to rise. This is called respiratory alkalosis. Several things can be happening to create this state, but a major player is CO2. CO2 dissolves in water (remember that water is also one of the results of metabolism) to become carbonic acid, which helps keep the blood acidic enough for oxygen to be released from hemoglobin.

So, what? Why would you care about this, and how does it impact you? As your breathing rate and volume increases beyond how quickly you are metabolising oxygen and sugar, your CO2 levels will start to drop — this is the definition of hyperventilation. We think of hyperventilation as breathing really fast and needing a paper bag to breathe into, but you can be hyperventilating on a low level all the time, which we call chronic hyperventilation. Besides the cold hands and feet, there are other impacts. If you are running (or practicing vigorous yoga, or cycling, or lifting heavy weights) and are breathing too much, your CO2 levels will drop, and your body won’t be able to access the oxygen it needs to fuel your cells, making activity more difficult and stressful. Over-breathing can also lead to more serious health issues, including asthma, metabolic disorders, or anxiety, depending on your genetic predisposition and history.

I was in the park this weekend with some friends, and the kids were running around. I was chatting with a couple of the kids (9-year-old boys) and I suggested they try running once around the park breathing only through their noses. I watched as they ran a loop around us, and when they got back, they looked surprised. One of the boys announced, “That was way easier!” His body was keeping in enough CO2 that it was more able to access oxygen in his muscles, and running was less strenuous.

Breathing is a habit — we breathe 20,000–30,000 times each day. If you have been habitually breathing more than you need to (even just a little bit more) for many years, it can take time to retrain your brain and body to breathe less. It can feel uncomfortable learning to breathe less, just like we feel discomfort when we try to change any habit.

How do you re-learn to breathe less? First of all, stop practicing breathing exercises where you are breathing a lot (hyperventilating), especially when you are just sitting still and not creating more CO2 to keep up with the rate of breathing. Second, start working on breathing through your nose all of the time. It’s harder to breathe more than you need to if you are only nose-breathing. You might need some support through a breath retraining course, but every little bit you do to start moving towards breathing less will help to keep your body and mind healthy.